Rick MacGregor and Jerrilynn Eby MacGregor, Stafford County, Virginia historians, visited the Hanover County, Virginia jail on March 12, 2019. We sincerely thank Mr. Art Taylor for an excellent tour of the building and for his enthusiastic sharing of Hanover County's history.

The writers are currently researching Stafford County's freestone industry. Because this stone is found throughout much of eastern Virginia and because many different types of structures have been built with it, we were interested in seeing the Hanover jail. The following thoughts are compiled with the intention of placing the jail within an overall context of the Aquia freestone industry that supplied building stone for the first and second generation of public buildings in Washington, DC.

Introduction

The Hanover County jail appears to be constructed of a type of sandstone generally known as Aquia freestone or Aquia stone. Geologists designate this as part of the Potomac Formation, which also includes sand, clay, and washed gravel. In certain areas, the sand has been compressed and cemented into stone; some of this is suitable for building purposes and some is not. Aquia stone forms a narrow belt that runs from the Potomac River southward nearly to the James River and passes through the counties of Prince William, Stafford, King George, Spotsylvania, Caroline, Hanover, Henrico, Chesterfield, and Prince George. A small amount is also found on the Nottoway River in Sussex County. Near the James River, the stone outcrops on Shockoe Creek and in the valleys of Gillis and Almond Creeks (Clark 92-93). Regardless of the location in which it is found, this particular type of sandstone is referred to as Aquia stone because Aquia Creek in Stafford County was the first location in which it is known to have been quarried.

As a general rule, Aquia freestone weighs about 130 pounds per cubic foot, varying slightly with moisture content, density, and other factors. For comparison, granite averages about 175 pounds per cubic foot. In the Stafford area, Aquia stone varies in color from white, light grey, tan, or rosy beige, the rather distinctive hues being the result of microscopic feldspar and iron particles interspersed throughout the material. In some instances, the stone is nearly white when first quarried, but may take on a tan or pale rosy color as the iron particles oxidize. Some of the stone in the Hanover jail is slightly greenish in color, which may be due to the presence of some other mineral. A chemical analysis of the stone might reveal the source of that color.

In Aquia stone the sand grains often have the appearance of having been laid down in layers, though cross-sections not uncommonly show swirls in the grain. Benjamin Henry Latrobe was of the opinion that the sand had been piled along an ancient shoreline by the action of wind more than by water (Latrobe, "On the Freestone" 298). In some instances, these layers, more correctly called bedding planes, may not be apparent when the stone is first cut. However, after exposure to air and water, the layers often become clearly visible. Sometimes the swirled iron particles provide interesting patterning in finished pieces of stone. This is especially evident in stone that has been sawn across the grain as opposed to being split with it. The old stonecutters and masons were well aware of freestone's characteristic bedding planes and, when possible, used them to advantage when cutting and setting the stone.

In most instances, masons laid freestone with the bedding planes in a horizontal orientation. Turning them the other way may encourage water to enter between the layers and hasten spalling or deterioration of the outermost surface of the stone. Freestone placed in the lower part of a wall is sometimes prone to spalling because it is more likely to stay damp and, thus, is more susceptible to the freeze-thaw cycle than drier stone located higher in the wall. It appears that some of the blocks on the lower course of the Hanover jail's south wall may have been laid with the bedding planes perpendicular to the ground.

Freestone is relatively soft when cut and is described as "green" when first taken from the ground. It hardens slowly upon exposure to the air. The water held within the stone, sometimes called "quarry sap," contains silica. As the water evaporates from the outer layer of the stone, the silica remains. This acts to cement the grains together and creates a hard, outer skin. The high silica content makes freestone less susceptible to acid rain than some other types of stone (McGee "Federal" 3). The action of hammering, chiseling, or picking blocks of stone to create a "finished" surface causes microscopic stress fractures withyin the top quarter-inch or so of the block. In some instances, water can penetrate these fractures and upon freezing result in spalling. Again, this is more frequently seen in blocks that are positioned in such a way that they don't dry completely. This may also be a contributing factor to the spalling observed in the jail's south wall. While this detracts from the aesthetics of the stone, it is usually confined to surface areas and rarely causes structural problems.

The quality and hardness of Aquia stone varies greatly from quarry to quarry and even from areas within the same quarry pit. Some deposits contain exceptional, fine-grained, solid stone that is ideal for carving or fine finishing. The stone in other deposits may contain rounded pebbles, clay nodules, bits of iron ore, or pieces of wood that have the appearance of having been burned. Some of this stone is soft and poorly cemented and doesn't weather well, even in its natural state.

In Stafford County freestone normally outcrops along hillsides and at the heads of ravines. Aquia Creek is a tributary of the Potomac River and is navigable for an extended distance. Aquia freestone outcrops all along the hills flanking Aquia Creek and was quickly noticed by colonial settlers as they explored the area. Because they had been working with a nearly identical material in England since antiquity, the early comers immediately recognized the stone. Patents were issued for land along Aquia Creek as early as 1651 and it was then first part of what would become Stafford County to be settled. Sometime thereafter, use of this local stone commenced, most likely for grave markers, building foundations, and chimneys.

Exactly when commercial freestone quarrying began in Stafford isn't known. A variety of finely finished grave markers from the 1680's attest to it having been cut and carved at least that early. It soon became an industry and, with few interludes, continued until 1930.

By 1791, Aquia stone from Stafford had been selected as the building stone for the new capital city of Washington. The President's House (now called the White House)(completed c. 1800) and the Capitol (1830) were the first two structures in the city built with this material. It was also used later for the U.S. Patent Office (1836), Treasury Building (1836), Post Office Building (1842), and the Long Bridge (1809). Aquia Stone was also shipped to other cities along the east coast and used in construction projects. Because this stone is easily quarried, easily worked, and is durable it was long popular as a building material.

Quarry Methods

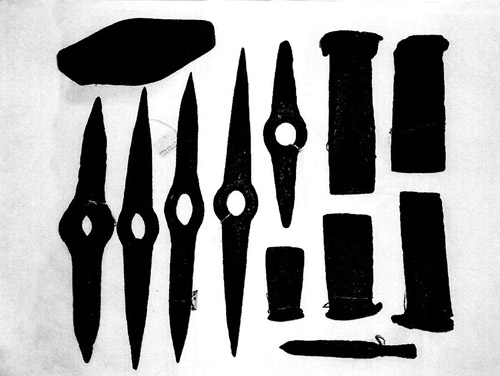

An assortment of typical quarry tools that have been recovered from Stafford County quarries. Included are picks, wedges of various sizes, the head of a stone hammer, and a chisel. An assortment of typical quarry tools that have been recovered from Stafford County quarries. Included are picks, wedges of various sizes, the head of a stone hammer, and a chisel. |

|

The methods utilized in the Stafford quarries were ancient and examples of these methods may be found at historic sites around the world. The tools were simple - someone wishing to obtain stone to put a foundation beneath his house needed little more than an agricultural pick and perhaps a wedge, hammer, and chisel. As quarrying became an industry, more specialized tools were made, but all were of the tried-and-true ancient designs and all were simple.

The first step in quarrying involved the removal of the overburden, a layer of dirt, pebbles, and vegetation on top of the deposit. This varied in thickness from a few inches to many feet, but had to be removed so that blocks of stone could be split from the exposed face. As quarrying continued, stone was removed farther back into the hill until the deposit was exhausted or the site became too difficult to work.

Once the deposit was cleared of overburden, a worker using a long-handled iron pick cut a channel (actually called a "groove") straight back into the stone. These grooves were 18 to 20 inches wide, the width of a man's shoulders. The groove extended back into the deposit for some feet, depending upon the size of the block they hoped to cut. The depth of the groove might be a few feet to 12 feet or more. |

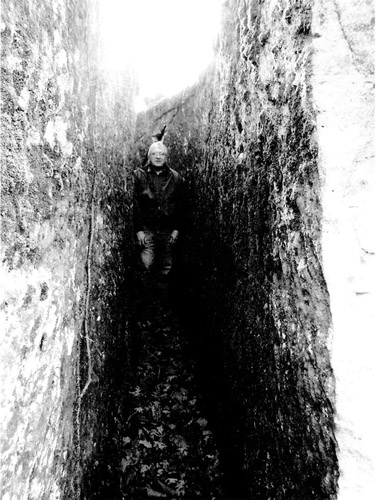

The worker then moved down the face of the deposit and cut a second groove parallel with the first, the distance between the two dependant upon the desired length of the block. Finally, he cut a third groove at the rear of the work area to connect the first two, thereby creating a large square of rectangular mass. The masses so delineated would then be split down into smaller pieces. At this point, workers used picks to create a narrow horizontal channel along the front face of the block. This was just wide enough to accomodate a row of wedges and was usually positioned just a few feet below the top edge of the block. The wedges were then pounded into this channel and, if all went well, the block would pop free. An old term for this method of quarrying was "grooving and lofting."  One of the quarry pits on Brent's Island in Stafford County. The channel describing the length and width of a block is still obvious as is the horizontal groove into which iron picks could be hammered to cause smaller blocks to split. One of the quarry pits on Brent's Island in Stafford County. The channel describing the length and width of a block is still obvious as is the horizontal groove into which iron picks could be hammered to cause smaller blocks to split. |

|

A man wielding a stone pick cut this typical groove into an outcropping of Aquia stone in Stafford County. The groove remains about eight feet deep, but may be partially filled with dirt and debris and may have been deeper. For some reason, this quarry was abandoned before pieces could be split from the prepared area. A man wielding a stone pick cut this typical groove into an outcropping of Aquia stone in Stafford County. The groove remains about eight feet deep, but may be partially filled with dirt and debris and may have been deeper. For some reason, this quarry was abandoned before pieces could be split from the prepared area. |

Blocks thus split were still often too large and required further reduction. This was done by wedge notching. The pick (or sometimes a chisel) was used to create a row of notches into which wedges were hammered. This caused the stone to break along the row and could be used to split stone either with or against the bedding planes. Often times, wedge notching was used instead of the straight channel described above. Both worked, but choosing one method over the other may have been a matter of personal preference on the part of the workers. In Stafford surviving evidence suggests that wedge notching predominated.

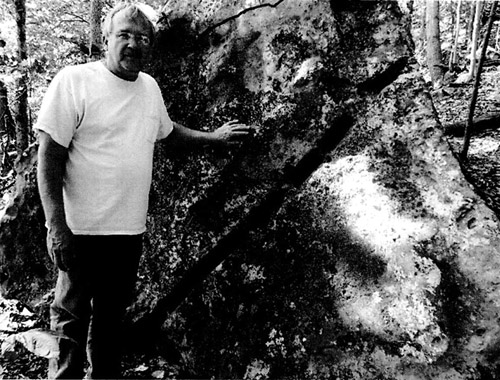

The particular piece of freestone to the right seems to have broken loose from the deposit and rolled down the hill, possibly during the quarrying process. It was left where it landed. Wedge notching was the most common method used to split large pieces of stone into more manageable pieces, but it is rare to see an example that hasn't been split. Quarriers used a pick to cut a row of notches along the line where they wanted the stone to split. Iron wedges driven into each notch forced the stone to break along that line. |

|

Photograph taken at Gibson's Quarry on Aquia Creek in Stafford County. Photograph taken at Gibson's Quarry on Aquia Creek in Stafford County. |

Moving the Stone

Once the stone had been worked down to manageable sized pieces, it was moved from the quarry pit to work areas where it could be further refined. At larger facilities, cranes were used to lift the blocks and transfer them out of the way of the quarry workers. Smaller quarries likely had blocks and tackle to aid lifting the heavy pieces. Normally, people endeavored not to move stone overland any further than absolutely necessary. Because Aquia stone typically is found in hillsides and on or near navigable water, a block could be placed on top of several poles and rolled to the nearest boat landing. It's surprisingly easy to roll a large piece of stone on poles. Smaller pieces might be put on stone sleds or loaded into ox carts for the the trip to the water. The water at most of the quarry landings on Aquia Creek was quite shallow. Normally, stone was transferred from the landing to shallow-draft scows that carried it to deep-water landings where it was loaded onto larger sailing vessels. These landings seem often to have had cranes for shifting the stone from the scows to the ships. One would expect to find the quarry that provided the stone for the Hanover jail not too far from the building. The dimensions and weights of three of the larger blocks in the building follow:

24" x 27" x 64" = 3,120 pounds

24" x 20" x 68" = 2,455 pounds

23" x 22" x 51" = 1,941 pounds |

This was a considerable amount to move by cart, sled, or by rolling on poles. A fully loaded scow didn't usually draw more than four feet of water. In very shallow water, quarriers could lighten the load so that it drew even less. If at all possible, the builder of the jail would have moved the stone at least part of the way by boat. The Hanover Jail Building

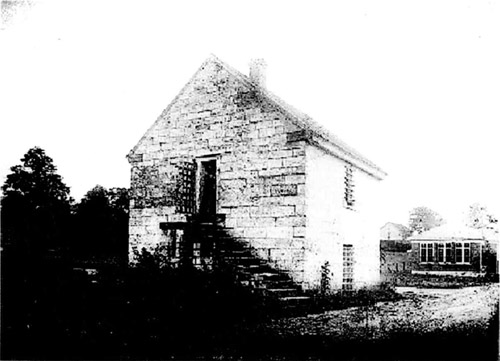

The Hanover jail was constructed with exceptional care. Each block was picked square and laid up in courses of uniform thickness rather than being built using randomly sized blocks or with stone rubble, which was common in utilitarian buildings such as a jail. What is believed to be the remains of an early jail in Fredericksburg is also of coursed stone. Surviving tool marks show that some of the blocks used in the building were also dressed with chisels.

Additional finish work was done to the edges of many of the blocks. A chisel was used to create an edging about a half-inch wide all the way around some of the blocks. This extra dressing was not observed on every block.

The blocks are placed upon a foundation that extends a few inches beyond the dimensions of the building's walls. Contrasting with the tan to greenish-grey blocks, this lowest course is almost charcoal grey in color The wider foundation acts as a water table, but the writers wonder if it may actually be the base of an earlier building. Given Hanover's long history, there must have been a previous jail somewhere near the courthouse.

At least two iron shims were used to level the blocks during the building process and these remain embedded in the mortar.

At some point, the jail appears to have been whitewashed. Most of this has weathered away leaving telltale evidence in small dimples on the blocks.

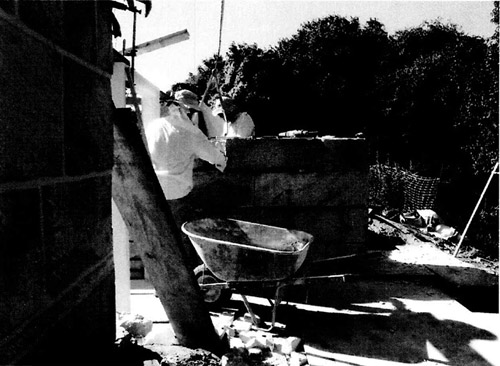

Aquia freestone blocks being set on the reconstructed foundation of the Washington house at Ferry Farm, Stafford County. Note the tongs that have just been used to place one of the blocks. Aquia freestone blocks being set on the reconstructed foundation of the Washington house at Ferry Farm, Stafford County. Note the tongs that have just been used to place one of the blocks. |

|

Many of the blocks retain angled holes that were drilled for the purpose of lifting them. A small crane or boom was likely erected next to the building site. Once a layer of mortar was applied and leveled, the crane, fitted with a set of tongs, lifted the block and set it carefully on top of the mortar. While the holes appear to be "upside down," they are, in fact, oriented correctly as the tongs were shaped in such a way that upon lifting they pinched the block and held it. Once tension was removed from the tongs, they slipped easily from the holes. During reconstruction of the foundation of the Washington house at Ferry Farm, the stone blocks were drilled in the same manner as seen in the Hanover jail. A motorized lift fitted with tongs picked up the blocks and placed them where the masons wanted them.

Also visible in a number of the blocks in the jail is scarring from drilling. In antebellum Stafford, wedge notching was the most frequently used method to split freestone from the deposits. This changed after the Civil War when slaves were not longer available to do the work. While steam-powered channeling machines were utilized in one large Stafford quarry, cheaper drilling may have been used in smaller facilities. |

Because the half-round scars found on the jail are small and short, the writers are of the opinion that plugs and feathers were used to split already quarried stone into blocks of the desired size. If Hanover historians can locate the quarry from which this material came, surviving tool marks there will likely reveal the method used to extract them.

Next to the heat pump at the jail is a broken piece of freestone with hand-cut mortises. This appears to have come from an upstairs window on the east (?) side of the building where a patch is now visible. The mortises likely held the iron window bars.

Stafford County also had a jail constructed of freestone, but it differed from Hanover's in several ways. This building had one cell on the lower level and a second one upstairs. Access to the second story was by way of a set of freestone steps on the north side of the building. It stood to the immediate east of the courthouse and in the middle of what is now U.S. Route 1. Stone for the jail was rubble material from Tyler's Quarry located about a half-mile north of Stafford Courthouse. Even as a brand new building, it was notoriously insecure and prisoners frequently escaped. |

|

The Stafford County jail was completed c. 1783 and was destroyed in 1923 for construction of U.S. Route 1. The Stafford County jail was completed c. 1783 and was destroyed in 1923 for construction of U.S. Route 1. |

Click here to see more about Hanover County's Old Stone Jail!

|